This project uses Natural Language Processing to quantitatively compare the Rider-Waite and Thoth Tarot systems by measuring the "Barnum effect," defined as the clustering of their divinatory meanings. The analysis concludes that the Thoth Tarot has more distinct and less ambiguous meanings, making it the more effective divination system according to this model.

Table of Contents

- Part 0: Introduction

- Which Tarot is Better?

- Avoiding Mystical Controversy

- Project Overview

- Part 1: Theory

- The Basic Model of Divination

- The Barnum Effect

- Establishing the Theory

- Quantifying the Barnum Effect

- Part 2: Experiment

- Text Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Tokenization and Cleaning

- Feature Extraction

- Dimensionality Reduction

- Averaging Word Embeddings

- Calculating the Clustering Coefficient

- Part 3: Conclusion

- References

Part 0: Introduction

Which Tarot is Better?

The question of which system—Waite or Thoth—holds the top spot in the world of Tarot has long been an unresolved issue in the occult community.

The Rider-Waite Tarot was designed by the mystic Arthur Edward Waite and illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith, a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. It was published by the Rider Company in 1909. As a successor to the ancient Tarot of Marseilles, it is the most widespread and influential system.

The Thoth Tarot was designed by the mystic Aleister Crowley and illustrated by Lady Frieda Harris, named after the ancient Egyptian god of wisdom, Thoth. It was used internally within Thelema in the early 20th century and was publicly released by the Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.) in 1969. It is often considered an advanced Tarot for spiritual practitioners.

Image: Arthur Edward Waite | Pamela Colman Smith | Aleister Crowley | Lady Frieda Harris

Image: Arthur Edward Waite | Pamela Colman Smith | Aleister Crowley | Lady Frieda Harris

Proponents of the former argue that the Waite Tarot is accessible, clear, and concise, making the renowned Waite system a universal and orthodox mystical masterpiece. Compared to the classic structure of the Waite system, the Thoth system is seen as obscure, deliberately mysterious, and an unorthodox path. Some even bluntly call the Thoth Tarot "unprofessional."

However, to the enthusiasts of the latter, although the Thoth deck was published later, its essence is more ancient, tracing back to Imhotep of the Third Dynasty of Egypt and even the mythical lost Book of Thoth. They claim this deck is profoundly wise, endlessly mutable, and unfathomable. In addition to its high aesthetic value, it is said to hold the true teachings of Heka and Jewish Kabbalah (קַבָּלָה). The Waite Tarot, in their view, is merely a simplified, fleeting version of ancient magic in a lesser age.

Image: Comparison of cards in the same position: Waite's "Temperance" vs. Thoth's "Art," Waite's "Strength" vs. Thoth's "Lust"

Image: Comparison of cards in the same position: Waite's "Temperance" vs. Thoth's "Art," Waite's "Strength" vs. Thoth's "Lust"

The question of "which Tarot is better" nearly tore the entire occult world in two during the internal disputes of the Golden Dawn. In the 20th century, an age illuminated by the light of reason, neither Waite fans nor Thoth devotees could truly refute the other or even capture mainstream attention, relying instead on esoteric evidence to defend their positions. Thus, the question remains unanswered today. Perhaps, by setting aside the transcendental fantasies of sympathetic magic, Gnosticism, and Hermeticism, we can catch a glimpse of the stunning brilliance beneath the mystical veil in an unexpectedly calm manner.

Image: Shuffled Tarot cards: Top - Thoth, Bottom - Waite

Image: Shuffled Tarot cards: Top - Thoth, Bottom - Waite

Avoiding Mystical Controversy

- Adherence to Materialism: We remain skeptical of unprovable or unfalsifiable principles of divination (e.g., Jungian collective unconscious, synchronicity, quantum entanglement).

- Divination as a Cultural Phenomenon: As Sir James Frazer described in The Golden Bough, the enduring nature of magic and divination, which has sustained humanity through its darkest hours, makes it a cultural phenomenon worthy of study.

- An Effective Divination System: An effective divination system should be as unambiguous as possible, containing distinct meanings to help individuals make more decisive choices and alleviate anxiety.

Project Overview

In this mini-project, I attempt to evaluate the quality of divination systems using methods from Natural Language Processing (NLP).

After delving into the mechanics of divination, I based my approach on the Barnum effect, using Word2Vec embeddings to create and analyze clusters of "divinatory meanings." The results of this analysis suggest that this model can quantitatively assess the quality of a divination system, with the potential for application in other areas of mystical research.

Part 1: Theory

The Basic Model of Divination

How can we quantitatively analyze a divination system? The first step, I believe, is to understand the basic model of divination.

In the realm of science, the application of a statistical model can be roughly summarized as: Data -> Model -> Output -> Expert Interpretation. Within the model are algorithms based on mathematical principles that process raw data.

[Data] ----> [Model (contains: Algorithm)] ----> [Output] ----> [Combine with reality]Basic framework of a statistical model application

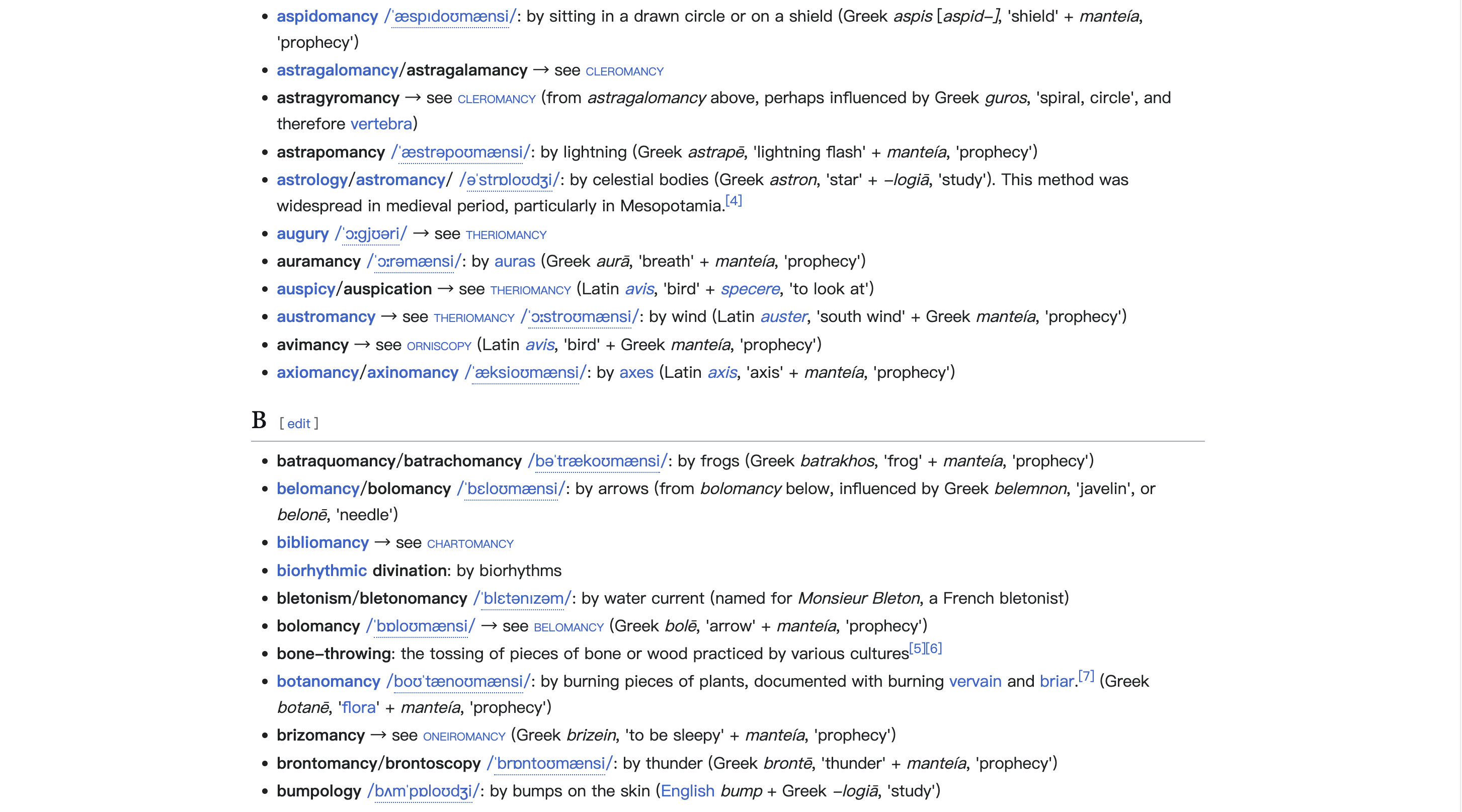

In contrast, each step of a divination reading appears much simpler. The initial "data collection" phase merely involves various methods (burning turtle shells, casting yarrow stalks, flipping coins, drawing lots...) to generate or simulate a random process. In mystical thought, randomness is the will of the gods or spirits.

Image: Methods of generating random seeds in various divination systems

Image: Methods of generating random seeds in various divination systems

We cannot use metrics like the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) or the F1-score from a confusion matrix to measure the effectiveness of divination, as the interpretation of a 卦 (divinatory symbol) varies from one practitioner to another. As far back as the era of King Wu Ding of the Shang Dynasty (c. 1200 BCE), a major headache for the king was the conflicting interpretations of the same crack on a turtle shell by his three senior diviners.

Image: Shang Dynasty oracle bone

Image: Shang Dynasty oracle bone

What remains constant in any divination system is a set of random seeds and their corresponding meanings.

Throughout countless centuries, these random seeds have been called the Six Yao, the Sixty-Four Hexagrams, the Hundred Lots of Guanyin, the Riddles of the Pythia, the Seventy-Two Pillars of Solomon, or the seventy-eight cards of the Tarot. For Joseph, who interpreted the Pharaoh's dream of seven fat and seven lean years; for Li Chunfeng, who felt the rise and fall of the Tang Empire in the wind; and for Nostradamus, who foresaw the centuries by gazing into the fire, the symbolic combinations of dreams, the direction and speed of the wind, and the dancing of flames were the indispensable random seeds of divination.

Image: Melisandre foresees the future in the flames | The "High Priestess" card from a Game of Thrones Tarot

Image: Melisandre foresees the future in the flames | The "High Priestess" card from a Game of Thrones Tarot

Some random seeds, such as birth dates and times (Bazi), bone structure (physiognomy), or palm lines (palmistry), are often mistaken for data. In reality, they are just special random numbers generated from the querent's own attributes, with their underlying principles being equally inexplicable. Our ancestors believed it was these random seeds that held the power to communicate between humans and the divine.

The number of random seeds is often derived from calculations involving sacred numbers within that culture. The meanings pointed to by these seeds may overlap, exhibiting one-to-many or many-to-one relationships. In a good divination system, we hope these meanings can cover various aspects of life while also possessing a degree of abstraction, allowing the system to handle vastly different situations.

If we were to make an analogy, these meanings are like parameters pre-trained on the accumulated experience of occult groups over many years, compiled into books by great masters, and continuously refined through trial and error. This allows them to achieve performances on new "test sets" that foster belief. These parameters, expressed in natural language, provide significant room for the diviner's personal interpretation (applying it to the specific situation), which enabled them to command the elements, control public opinion, and even manipulate rulers for millennia in the dawn of civilization, exploiting people's fear and ignorance.

Image: An Aztec priest harms the health of others in the name of divination

Image: An Aztec priest harms the health of others in the name of divination

Thus, we have clarified the basic form of a divination system: Random Seed -> Model -> Meaning -> Diviner's Interpretation.

[Random Seed] ----> [Model (Imagery & Symbolism)] ----> [Combine with Reality]The basic form of a divination system

The "model" part of a divination system is empty; or rather, the only "algorithm" is the mapping from the random seed to its meaning. In this highly associative link, the meaning serves as a highly condensed repository of cultural connotations, playing a key role as the unchanging factor amidst change.

The Barnum Effect

To quantify the quality of divination, let's consider the opposite. When would people say a divination reading is meaningless?

Tarot and astrology practitioners often encounter an irrefutable jab: "Ha! That's just the Barnum effect. This reading is meaningless."

The Barnum effect is a common psychological phenomenon whereby individuals give high accuracy ratings to descriptions of their personality that supposedly are tailored specifically for them, but are, in fact, vague and general enough to apply to a wide range of people. This effect can provide a partial explanation for the widespread acceptance of some paranormal beliefs and practices, such as astrology, fortune telling, aura reading, and some types of personality tests.

— Paul E. Meehl, 1956

Since the Barnum effect (known in ancient China as qian long wen qu, or "flattery and ambiguity") is strong evidence that a divination is unreliable or "bad," if we can measure its degree, it naturally serves as a tool to evaluate the quality of a divination system. Therefore, the Barnum effect became my breakthrough and theoretical pillar for quantifying divination.

Establishing the Theory

From the perspective of the Barnum effect, the similarity of meanings is the fundamental criterion for whether a divination (an assessment of one's personality or future) is vague.

For example, suppose a Tang Dynasty scholar and a female swordswoman want to know their futures. They consult two people: Zhang, a lame fortune-teller in the village, and Yuan Tiangang, a master of Taoist arts. Each uses their own divination system.

Zhang to the scholar (draws Hexagram A): Your future holds uncertainty. You may experience great storms, while at other times it may seem uneventful. You will go through many things and feel both pain and joy.

Zhang to the swordswoman (draws Hexagram B): Your future may see great storms and is uncertain. At other times, it may seem uneventful. You will experience many things and feel joy as well as pain.

Yuan Tiangang to the scholar (draws Hexagram A): You will pass the imperial examination at the age of twenty and become a prime minister when the new emperor ascends the throne. You will have a feud with the Gao family and marry into the Lu family. Your health will be good until the age of fifty-two, after which your life will be in peril.

Yuan Tiangang to the swordswoman (draws Hexagram B): You will slay your enemy within a year, find your master on the shores of the East China Sea, and settle on a mountain covered with catalpa trees. At the age of sixty, you will achieve immortality.

If a person receives very similar meanings regardless of the hexagram (random seed) they draw, making all outcomes indistinguishable, the divination is not just poor—it's utterly meaningless. The meanings have maximum similarity, all clustered together. This is the "most Barnum" scenario. Conversely, if the meanings are relatively dispersed, the divination system is "less Barnum."

Zhang's divination system is terrible; his statements are universally applicable. All hexagrams (random seeds) point to similar meanings, or in other words, all meanings are clustered in one place. The querent has gained nothing from the reading.

In contrast, Yuan Tiangang's pronouncements are highly specific, and his meanings are dispersed. Different hexagrams lead to completely different conclusions. The two Tang-era querents would surely agree that his is a better divination system.

Comparing the similarity between meanings, if done by a human, would require scoring the closeness of every word pair and creating a massive table to observe patterns. Trying to identify clusters of meaning this way would be an almost unimaginable task.

However, today we have numerous methods from the field of deep learning to process natural language data. When it comes to clustering similar words and separating dissimilar ones, Word Embedding Clustering is an excellent approach.

Quantifying the Barnum Effect

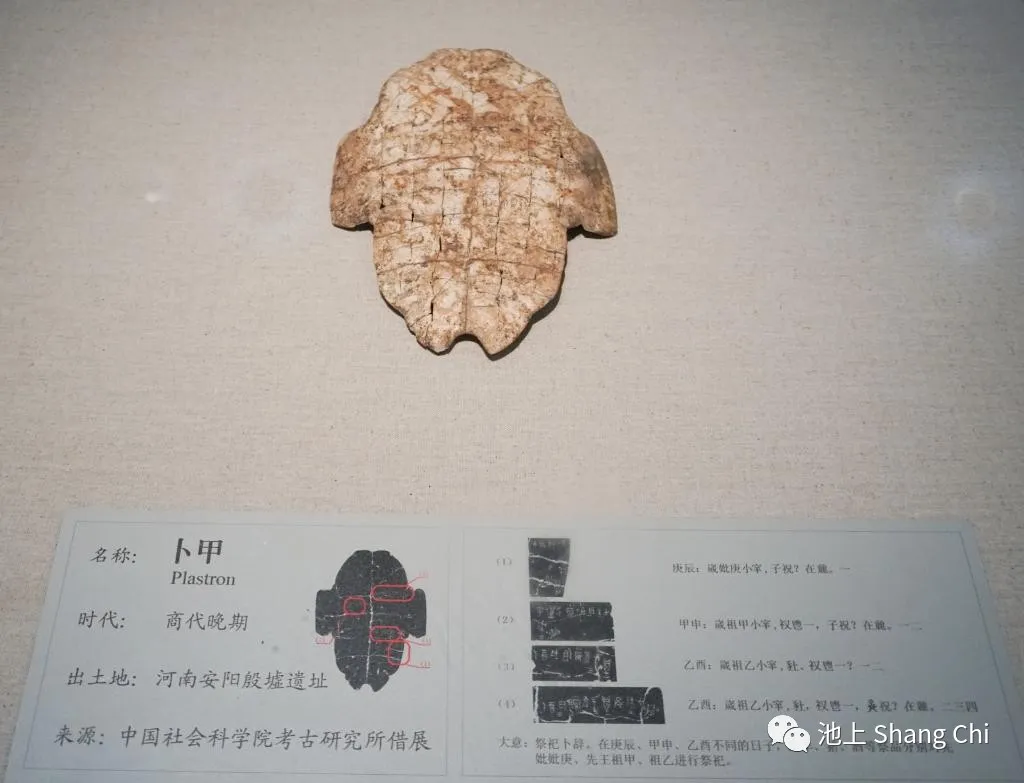

Using word embedding clustering, we can quantify the Barnum effect.

In Natural Language Processing (NLP), a word embedding is a representation of a word used for text analysis, typically in the form of a real-valued vector that encodes the word's meaning. Words that are closer in the vector space (i.e., share common contexts in a text corpus) are expected to have similar meanings. In 2013, a team at Google led by Tomas Mikolov created Word2Vec, which can train vector space models much faster than previous methods and is widely used in experiments.

Image: Cosine similarity between vectors represents semantic relevance

Image: Cosine similarity between vectors represents semantic relevance

For instance, in the example above, the tensor of meanings for "Zhang's" divination system would be completely clustered together in the semantic space, indicating that the meanings are indistinct and the system's effectiveness is low. In contrast, the tensor for Yuan Tiangang's system would be largely dispersed, showing distinct meanings and high effectiveness. Therefore, to evaluate a divination system from the perspective of the Barnum effect, we only need to analyze the distribution of its meanings in the semantic space, including the optimal number of clusters, their distribution, and the global clustering coefficient.

Let's define the Barnum Coefficient as the Global Clustering Coefficient of the "divinatory meaning" space.

In graph theory, the clustering coefficient is a measure of the degree to which nodes in a graph tend to cluster together. The global clustering coefficient is based on triplets of nodes. A triplet is three nodes that are connected by either two (an open triplet) or three (a closed triplet) undirected ties. This metric indicates the clustering in the entire network (globally) and can be applied to both undirected and directed networks. The global clustering coefficient is defined as:

For an undirected graph with adjacency matrix , the global clustering coefficient can also be written as

where is the degree of node . We use the global clustering coefficient of the "divinatory meaning" semantic space—the Barnum Coefficient—along with the distribution of clusters, to judge the effectiveness of the divination system.

Part 2: Experiment

Required Libraries

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import missingno as msno

from gensim.models.word2vec import Word2Vec

import gensim.downloader as api

from pandas.plotting import scatter_matrix as scmx

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

from adjustText import adjust_text

from sklearn.cluster import KMeans

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

from sklearn.manifold import TSNE

from gc import callbacks

import wandb

from wandb.keras import WandbCallback

wandb.init()Text Acquisition and Preprocessing

We use the English original texts of The Pictorial Key to the Tarot (1975 edition) by Rider-Waite founder Arthur Edward Waite and The Book of Thoth: A Short Essay on the Tarot of the Egyptians (1944 edition) by Thoth Tarot founder Aleister Crowley. Both are authoritative reference books for their respective Tarot card interpretations.

Since Tarot books often contain theoretical discussions and other content not relevant to card meanings, we need to be selective. For the Waite Tarot, we select the following sections from The Pictorial Key to the Tarot:

- The Doctrine of the Veil (containing all 78 cards)

- The Outer Methods of the Oracles (i.e., special card spreads)

For the Thoth Tarot, we select the following sections from Crowley's Book of Thoth:

- The Atu, the Keys or Trumps (i.e., the Major Arcana)

- The Court Cards

- The Small Cards (i.e., the Minor Arcana excluding Court Cards)

Each Tarot deck consists of 22 Major Arcana and 56 Minor Arcana.

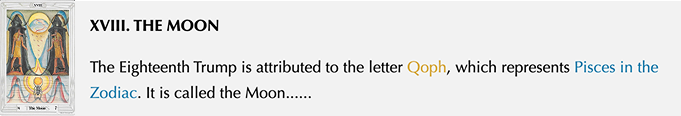

Image: Opening text for the Thoth Tarot's "Moon" card. The highlighted parts are Kabbalistic and astrological terms, not part of the divinatory meaning.

Image: Opening text for the Thoth Tarot's "Moon" card. The highlighted parts are Kabbalistic and astrological terms, not part of the divinatory meaning.

We remove the introductory paragraphs of each section (which mainly consist of mystical terminology) and keep the abstract descriptive sentences that follow a "Card Meaning" delimiter. The meanings are imported segment by segment to form a data frame with 78 rows and several features.

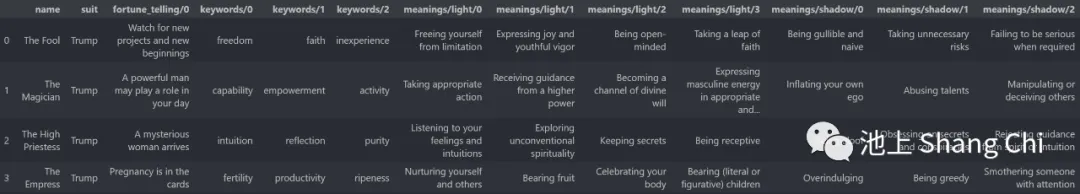

Image: The first 4 rows of the preprocessed meaning list for the Waite Tarot.

Image: The first 4 rows of the preprocessed meaning list for the Waite Tarot.

We define the primary meaning as the divinatory interpretation given by the diviner after explaining the card's symbolism, including fortunes and keywords from the book.

In addition to the primary meaning, the upright/reversed or light/shadow meanings have an equally important psychological impact on the querent. These two models are historically and statistically consistent.

For the Waite Tarot, the upright or reversed orientation of the card determines the interpretation. The Thoth Tarot does not use reversals, but if ascending element cards (Fire, Air) predominate in a reading, they are interpreted in their "light" aspect, while the descending elements (Water, Earth) are interpreted in their "shadow" aspect, and vice versa. The concepts of upright/light and reversed/shadow both originate from the light/dark aspects of the ancient Tarot of Marseilles, so they have a one-to-one correspondence, and both scenarios have an equal probability of occurring.

We combine the interpretations for each card into three meaning samples. The table below shows the samples for "The Moon" card from both systems:

| Divinatory Aspect | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Waite "Moon" Main | Watch for problems at the end of the month, mystery, fantasy, imagination. |

| Waite "Moon" Light | Enjoying healthy fantasies and daydreams. Using your imagination. Practicing magic or celebrating the magic of everyday life. |

| Waite "Moon" Shadow | Attuning yourself to the cycles of nature. Becoming unable to separate fantasy from reality. Suffering from delusions. Losing your appreciation for the fantastic or magical. |

| Thoth "Moon" Main | Go down to the world below, the journey goes into the deep unconscious. The mirror of the soul or the bridge between the inner and the outer world. |

| Thoth "Moon" Light | Devotion to intuitive knowledge. The strange path goes into the depths of the soul, confronts the night, with fears, understand yourself most profoundly. |

| Thoth "Moon" Shadow | Illusions, hysteria, complexities of abuse, hallucinations, fear, abuse of drugs, avoidance of reality. |

Tokenization and Cleaning

- Collapse a list of strings into one long string for processing.

- Tokenize the text into words.

- Convert all text to lowercase.

- Remove non-alphabetic tokens (e.g., punctuation).

- Filter out stopwords (common English words like 'is', 'a', 'that', which do not carry significant meaning).

# Get all keyword meanings

big_meaning_string = ' '

for col in wt_df[['meaning_main','meaning_light','meaning_shadow']]:

card_meanings = wt_df['keywords/0']

# Create a list of strings, one for each card

card_meaning_list = [meaning for meaning in card_meanings]

# Collapses a list of strings into one long string for processing

big_meaning_string = big_meaning_string.join(card_meaning_list)

import nltk

from nltk.tokenize import word_tokenize

# Tokenize the string into words

tokens = word_tokenize(big_meaning_string)

# Remove non-alphabetic tokens, such as punctuation

words = [word.lower() for word in tokens if word.isalpha()]

# Filter out stopwords

from nltk.corpus import stopwords

stop_words = set(stopwords.words('english'))

words = [word for word in words if not word in stop_words]Feature Extraction

Check pre-trained models

import gensim.downloader

print(list(gensim.downloader.info()['models'].keys()))Load Word2Vec

from gensim.models.word2vec import Word2Vec

import gensim.downloader as api

corpus = api.load('text8') # download the corpus and return it opened as an iterable

model = Word2Vec(corpus) # train a model from the corpusCheck model and word set

Economy_vec = model.wv['economy']

Economy_vec[:20] # the first 20 dimensions for the word "economy"

# array([-1.612369 , -1.3064319 , 3.3133252 , -0.42280877, -2.0245464 ,

# 0.79807955, 0.5534356 , 0.20746948, 0.01085902, 0.05076587,

# 0.09634769, 3.0803256 , -2.9690804 , 0.05802807, -0.1087971 ,

# -0.51553446, 0.36582315, 0.11390762, 1.0218401 , -0.8172747 ],

# dtype=float32)

words = words['0'].tolist()

words[:3] # first three words for card 0, the Fool

# ['infinite', 'disintegration', 'journey']Filter the vector list, keeping only vectors that exist in the Word2Vec model. Create a corresponding list of words. Zip the words and their vector representations into a dictionary to create a DataFrame.

The table below shows the position of the first word vector from the Thoth Tarot, "infinite," in the 100-dimensional semantic space.

| word_vec | 0 | 1 | 2 | ... | 99 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| infinite | 0.447215 | -2.056401 | 1.033373 | ... | -2.114104 |

1 row × 100 columns

# Filter the list of vectors to include only those that Word2Vec has a vector for

vector_list = [model.wv[word] for word in words if word in model.wv.key_to_index]

# Create a list of the words corresponding to these vectors

words_filtered = [word for word in words if word in model.wv.key_to_index]

# Zip the words together with their vector representations

word_vec_zip = zip(words_filtered, vector_list)

# Cast to a dict so we can turn it into a DataFrame

word_vec_dict = dict(word_vec_zip)

df = pd.DataFrame.from_dict(word_vec_dict, orient='index')

df.head(1)Dimensionality Reduction

t-SNE can be used to explore local neighbors and find clusters, allowing developers to ensure that an embedding preserves the underlying meaning in the data (e.g., in the MNIST dataset, you can see the same digits clustering together). Here, we use t-SNE for dimensionality reduction.

The parameters for t-SNE are important, as different values can produce very different results. I tested several perplexity values between 0 and 100 and found that they produced roughly the same shape each time. I also tested learning rates between 20 and 400 and decided to keep the default learning rate (200). For visibility and processing time, I used 260 samples instead of the full matrix.

from sklearn.manifold import TSNE

# Initialize t-SNE

tsne = TSNE(n_components = 3, init = 'random', random_state = 10, perplexity = 100)

# Use only 400 rows to shorten processing time

tsne_df = tsne.fit_transform(df[:400])

sns.set()

# Initialize figure

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize = (11.7, 8.27))

sns.scatterplot(x=tsne_df[:, 0], y=tsne_df[:, 1], alpha = 0.5)

# Import adjustText, initialize list of texts

from adjustText import adjust_text

texts = []

words_to_plot = list(np.arange(0, 400, 10))

# Append words to list

for word in words_to_plot:

texts.append(plt.text(tsne_df[word, 0], tsne_df[word, 1], df.index[word], fontsize = 14))

# Plot text using adjust_text (because overlapping text is hard to read)

adjust_text(texts, force_points = 0.4, force_text = 0.4,

expand_points = (2,1), expand_text = (1,2),

arrowprops = dict(arrowstyle = "-", color = 'black', lw = 0.5))

plt.show()Averaging Word Embeddings

Averaging word embeddings is a common method where each word in a sentence is weighted to overcome the weaknesses of simple averaging.

def document_vector(word2vec_model, doc):

# remove out-of-vocabulary words

doc = [word for word in doc if word in model.wv.key_to_index]

return np.mean(model.wv[doc], axis=0)

# Our earlier preprocessing was done when we were dealing only with word vectors

# Here, we need each document to remain a document

def preprocess(text):

text = text.lower()

doc = word_tokenize(text)

doc = [word for word in doc if word not in stop_words]

doc = [word for word in doc if word.isalpha()]

return doc

# Function that will help us drop documents that have no word vectors in word2vec

def has_vector_representation(word2vec_model, doc):

"""check if at least one word of the document is in the

word2vec dictionary"""

return not all(word not in word2vec_model.wv.key_to_index for word in doc)

# Filter out documents

def filter_docs(corpus, texts, condition_on_doc):

"""

Filter corpus and texts given the function condition_on_doc which takes a doc.

The document doc is kept if condition_on_doc(doc) is true.

"""

number_of_docs = len(corpus)

if texts is not None:

texts = [text for (text, doc) in zip(texts, corpus)

if condition_on_doc(doc)]

corpus = [doc for doc in corpus if condition_on_doc(doc)]

print("{} docs removed".format(number_of_docs - len(corpus)))

return (corpus, texts)

# Preprocess the corpus

corpus = [preprocess(title) for title in words]

# Remove docs that don't include any words in W2V's vocab

corpus, words = filter_docs(corpus, words, lambda doc: has_vector_representation(model, doc))

# Filter out any empty docs

corpus, words = filter_docs(corpus, words, lambda doc: (len(doc) != 0))

x = []

for doc in corpus: # append the vector for each document

x.append(document_vector(model, doc))

X = np.array(x) # list to array

# Initialize t-SNE

tsne = TSNE(n_components = 2, init = 'random', random_state = 10, perplexity = 100)

# Again use only 400 rows to shorten processing time

tsne_df = tsne.fit_transform(X[:400])Calculating the Clustering Coefficient

import networkx as nx

# Calculate cosine similarity

from sklearn.metrics.pairwise import cosine_similarity

# df2 = pd.read_csv("./100TTvec.csv").iloc[:,1:] # Example of loading vector data

# pd.DataFrame(cosine_similarity(df2)).to_csv("./cosinTT.csv") # Example of saving similarity matrix

# Assuming 'df' is a DataFrame where rows are word vectors and the index contains the word.

# We create an adjacency list from the cosine similarity matrix for graph creation.

# For simplicity, let's assume we have an edge list DataFrame 'edge_df' with columns 'source', 'target', 'weight'.

# G = nx.from_pandas_edgelist(edge_df, 'source', 'target')

# Here, we will simulate a graph creation from a DataFrame for demonstration.

# This part of the original code is not fully self-contained. The following is an interpretation.

# Let's assume 'df' is an edge list DataFrame with columns '1' and '2' representing connected nodes.

G = nx.Graph()

# G = nx.from_pandas_edgelist(df, '1','2') # This line requires df to be an edge list

# Let's create a sample graph for demonstration as the original is unclear

# Create a sample DataFrame that represents edges based on some criteria (e.g., high similarity)

similarity_matrix = cosine_similarity(df)

edge_list = []

for i in range(len(df.index)):

for j in range(i + 1, len(df.index)):

if similarity_matrix[i, j] > 0.5: # Example threshold

edge_list.append((df.index[i], df.index[j]))

G.add_edges_from(edge_list)

from matplotlib.pyplot import figure

figure(figsize = (10,8))

nx.draw_shell(G, with_labels = True)

# Calculate average clustering coefficient

cc = nx.average_clustering(G)

print(f"Average Clustering Coefficient: {cc}")

# Calculate clustering coefficient for each node

c = nx.clustering(G)Part 3: Conclusion

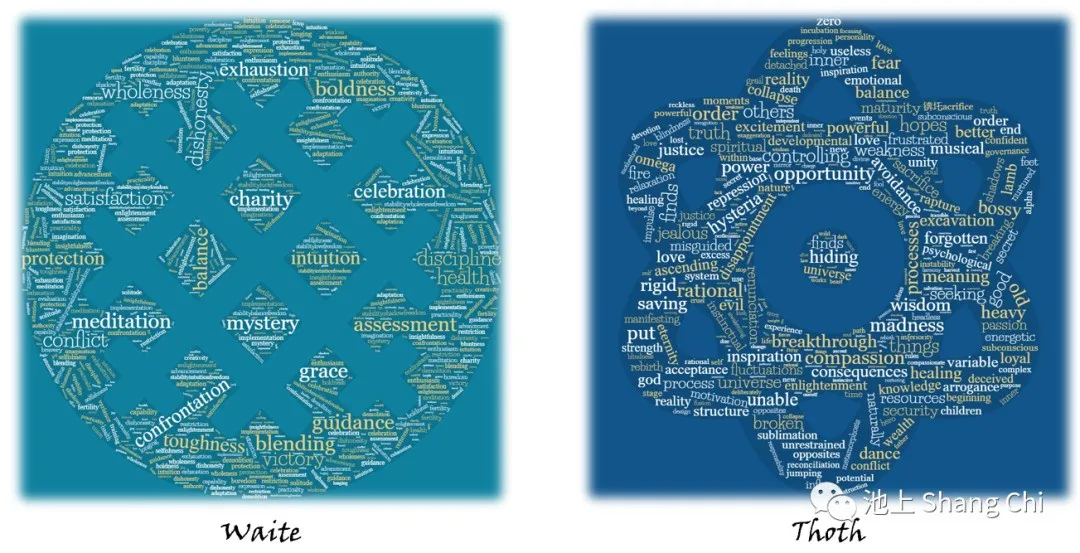

Image: Word clouds showing the composition and frequency of words in the Waite and Thoth Tarot texts.

Image: Word clouds showing the composition and frequency of words in the Waite and Thoth Tarot texts.

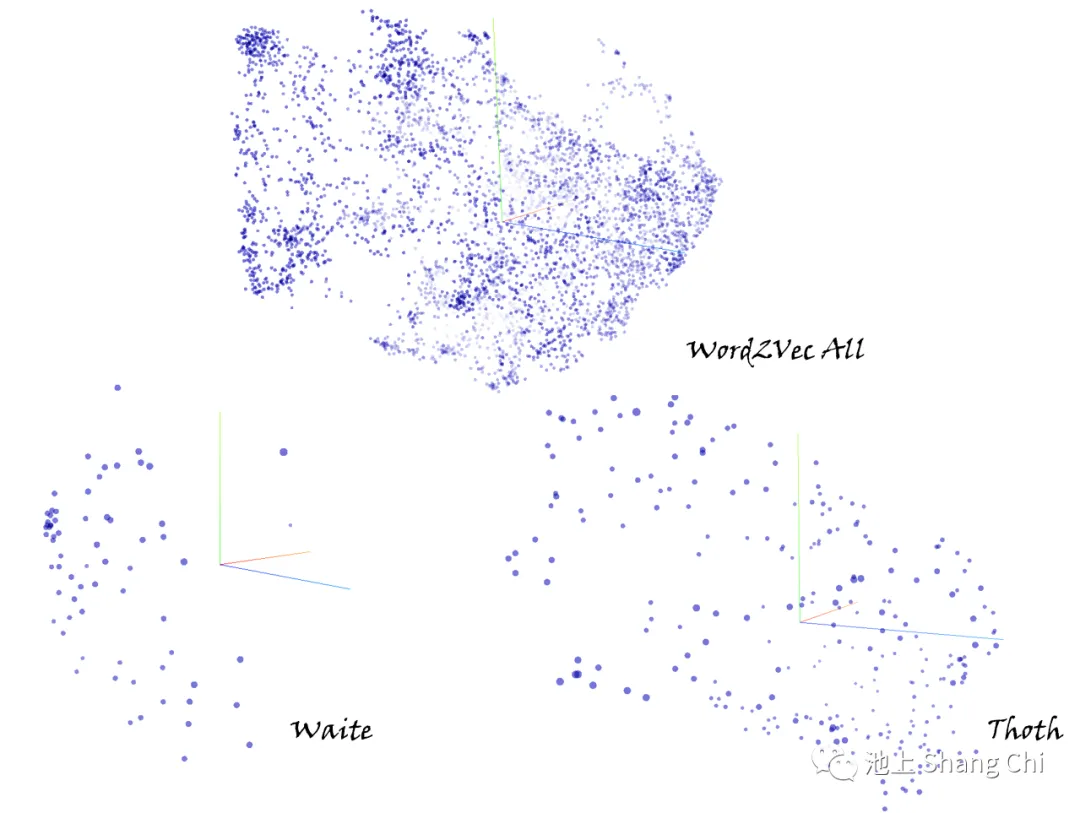

First, I separated the relevant meaning-related sections from the authoritative books of both systems into "main meaning," "light meaning," and "shadow meaning." Then, using Word2Vec for feature extraction, I mapped these meanings into a 100-dimensional semantic space. After applying t-SNE for dimensionality reduction to three dimensions for both Waite and Thoth, I observed that even with the same number of samples, the Waite vectors were more clustered, with many meanings overlapping, making it appear as if there were fewer points. The Thoth vectors, in contrast, were more separated and evenly distributed throughout the vector space. This indicates that the "divinatory meanings" of the Waite Tarot have a higher degree of clustering.

Image: 3D visualization of word vectors after t-SNE reduction: Top - Full Dictionary, Left - Waite, Right - Thoth

Image: 3D visualization of word vectors after t-SNE reduction: Top - Full Dictionary, Left - Waite, Right - Thoth

Image Collage:

A/B: Heatmaps of word vectors in 100D space for Waite and Thoth.

H/I: Elbow method scores for up to 100 clusters.

J/K: Elbow method scores for up to 15 clusters.

L/M: 3D distribution of word vectors for both systems.

N/O: 3D visualization with 6 clusters.

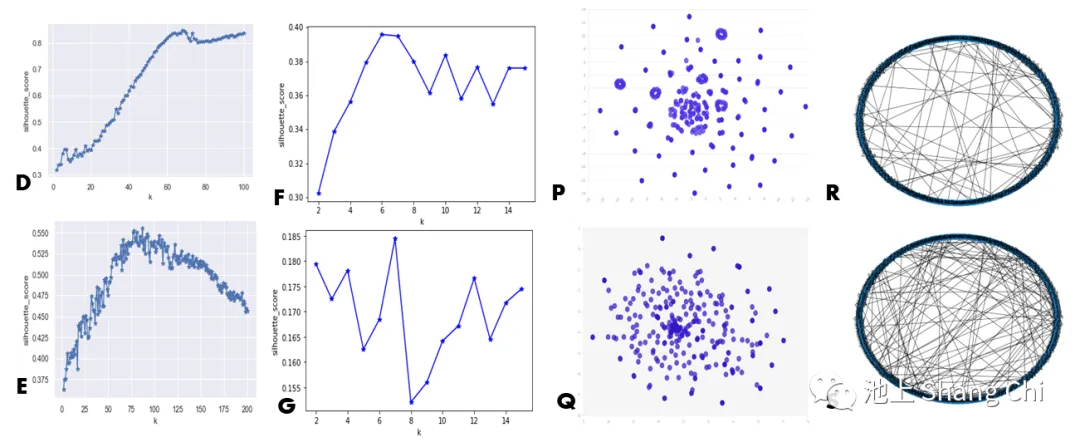

D: Silhouette scores for Waite (up to 100 clusters).

E: Silhouette scores for Thoth (up to 200 clusters).

F/G: Silhouette scores for both (up to 35 clusters).

P/Q: 2D scatter plots of reduced meaning vectors.

R/S: Graph representations of meaning distances.

Image Collage:

A/B: Heatmaps of word vectors in 100D space for Waite and Thoth.

H/I: Elbow method scores for up to 100 clusters.

J/K: Elbow method scores for up to 15 clusters.

L/M: 3D distribution of word vectors for both systems.

N/O: 3D visualization with 6 clusters.

D: Silhouette scores for Waite (up to 100 clusters).

E: Silhouette scores for Thoth (up to 200 clusters).

F/G: Silhouette scores for both (up to 35 clusters).

P/Q: 2D scatter plots of reduced meaning vectors.

R/S: Graph representations of meaning distances.

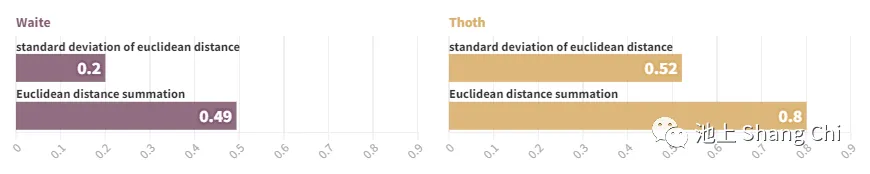

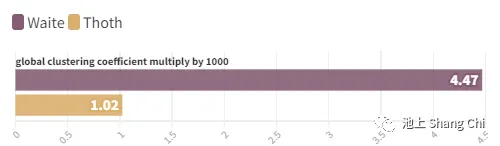

| Metric | Waite | Thoth |

|---|---|---|

| Global Clustering Coeff. | 0.00446828 | 0.00102407 |

| Average Cosine Similarity | 0.15194038 | 0.15295299 |

| Sum of Euclidean Distances | 0.493965 | 0.800989 |

| Std Dev of Euclidean Distances | 0.200233 | 0.521766 |

Image: Left/Right - Waite/Thoth; Top/Bottom - Std Dev of Euclidean Distance / Sum of Euclidean Distance

Image: Left/Right - Waite/Thoth; Top/Bottom - Std Dev of Euclidean Distance / Sum of Euclidean Distance

Image: Top/Bottom - Waite/Thoth Global Clustering Coefficient ( 1000)*

Image: Top/Bottom - Waite/Thoth Global Clustering Coefficient ( 1000)*

When using the elbow method to find the optimal number of clusters, the difference between the two systems was minimal, and neither showed a distinct "elbow" point. However, when using the silhouette method, the Waite Tarot achieved its optimal partition at 66 clusters with a high score of 0.87, which remained high thereafter. The Thoth Tarot only reached its optimal partition at 78 clusters, with a much lower score of 0.56, which then dropped rapidly. This suggests that the Waite Tarot's meanings are more easily divided into coherent clusters. The Waite Tarot also showed a significant increase in silhouette score around 6 clusters, which corresponds to the several circular clusters observed in its visualizations.

After reducing to two dimensions, we found that the Waite Tarot's meanings form several circular clusters, including some highly overlapping dark spots (which makes it appear to have fewer points). This shows that many card meanings in the Waite system are very similar. The central part consists of a dense core where these clusters are squeezed together, with a few meanings scattered far apart. In contrast, the Thoth system is characterized by a very high degree of clustering in a small core, which then drops off sharply towards the periphery. The Thoth system has a lower frequency of repeated words and synonyms, making it sparser overall.

The average cosine similarity between word vectors was slightly higher for the Waite system. The sum of Euclidean distances for Thoth was 2.5 times that of Waite. The standard deviation of Euclidean distances for Thoth was 1.5 times that of Waite. This indicates that the meanings in the Thoth system are farther apart but also more varied in their distances. Finally, I mapped the two word-embedding matrices to graphs and calculated their global clustering coefficients. The result was that the Waite Tarot's global clustering coefficient is 0.004468275, more than four times that of the Thoth Tarot (0.001024066).

In summary, the meanings of the Waite Tarot exhibit a higher degree of clustering. The distinctions between different divinatory meanings are smaller, and the same ideas appear more frequently across different card interpretations, making it more ambiguous. The Thoth system's meanings are more evenly distributed overall and are harder to partition into distinct clusters, with only a portion of meanings being tightly clustered.

Therefore, I conclude that between the two mainstream Tarot systems, the Thoth system is the more effective Tarot with more distinct meanings (from the perspective of the Barnum effect)—it is the "better Tarot." This might be related to the Thoth Tarot's deep and rich mystical lineage.

This exploration into evaluating a mystical system still has many limitations. For example, I did not create a cross-lingual comparison system, build a network or dictionary of mystical symbols, or invent a model specifically for this task. Many of the steps and methods could be optimized.

The fact that I was working with the same 78 cards, English texts of a similar era, and a streamlined "plug-and-play" workflow allowed this experiment to be completed in a short amount of time. If one were to attempt a quantitative comparison of systems like the I Ching, the Mātaṅga, or the Dorotheus of Sidon—with their ancient languages, numerous interpretations, and hard-to-reconstruct divination procedures—it would become another interesting problem altogether.

References

[1] Giles, C. The Tarot: History, Mystery, and Lore. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994.

[2] Frazer, J. G. & Fraser, R. The golden bough: a study in magic and religion. 3rd ed., Oxford University Press USA - OSO, 2009.

[3] Zhang, Yuwei. A Study of Royal and Non-Royal Sacrificial Divinations in the Oracle Bone Inscriptions of the Wu Ding Period. 2007.

[4] Meehl, P. E. "Problems in the actuarial characterization of a person." Psychological Bulletin, 53(5), 406–409, 1956.

[5] Mikolov, T. et al. "Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space." arXiv preprint arXiv:1301.3781, 2013.

[6] Mikolov T, Sutskever I, Chen K, et al. "Distributed representations of words and phrases and their compositionality." Advances in neural information processing systems, 26, 2013.

[7] Waite, A. E. The pictorial key to the tarot: being fragments of a secret tradition under the veil of divination. Weiser Books, 1975.

[8] Crowley, A. The Book of Thoth: A Short Essay on the Tarot of the Egyptians. Weiser Books, 1944.